Pugs are a very, very large group of Geometrid moths. Called Pugs, because the hindwings are stubby (pug-winged), the overall effect is the "soaring hawk" look that you can see in the photo here. Pugs are a notoriously difficult group of moths to identify; except apparently Eupithecia graefii. The person that confirmed this on Bug Guide mentioned the "red/brown distal spot" as a diagnostic feature. The Victoria Natural History Society expert, Jeremy Tatum concurred with this identification. Edward Graef was an entomologist from Brooklyn, NY that was very active in taxonomy and collecting in the late 1800's. The larvae of E. graefii feed on arbutus and manzanita and is relatively common along the west coast of North America. Most sightings and specimen collections of adults are from late April through the summer. That this one was out on February 15th speaks to the incredibly mild weather that we have been having.

0 Comments

Yellow-rumped Warblers are found here at Leaning Oaks in the spring and early summer and then essentially disappear for a month and then make an appearance on fall migration from mid-August until the end of September. They may well be here, only silent in the canopies of the Douglas-fir or perhaps they move up in elevation during those months. The Yellow-rumped Warbler has two distinct colour forms that used to be considered separate species: the "Myrtle" Warbler of the east and "Audubon’s" Warbler of the mountainous West. The Audubon’s has a yellow throat; in the Myrtle subspecies the throat is white. Female Audubon's have less boldly marked faces, lacking the dark ear patches of the "Myrtle" Warbler. We get both forms on migration, but the form that lingers here to breed is the "Audubon's" form.  This lichen (Cladonia bellidiflora) is found in a wide variety of habitats over much of the temperate regions in both the northern and southern hemisphere. Here at Leaning Oaks it was photographed on dead wood, growing in the company of other mosses and lichens. A number of species of Cladonia have the bright red fruiting structures or apothecia. A British website decribes this species rather elegantly: "Non-fruiting podetia often tall, generally unbranched, gradually tapered, terminating in points or small cups with red pycnidia, podetial surface clothed in densely layered, blue-green or yellow-green, palmately incised squamules that peel upwards and which diminish evenly in size from base to tip of the podetium, soredia absent; apothecia bright red, on shorter and more irregularly tapered and squamulose podetia.......for reasons I cannot quite explain reminds me of Japanse Pagodas."  The Western yellowjacket queens overwinter and usually emerge March to April when they go to look for a new nest. Apparently they won't reuse a nest from a previous year. The warm weather of the past few weeks may have brought this one out early - she was found in a malaise trap that we have on the property. Western yellowjackets (Vespula pensylvanica) are social, underground nesters and as many know, they will repeatedly sting and and aggressively protect these nests. There are records of nests (not at Leaning Oaks!) that have over 2000 workers in one nest! They can become a nuisance on their up years when the larvae start to grow and they require copious quantities of protein for which they aggressively scavenge! You know what I mean - no piece of salmon goes untouched. In their quest for proteins they do feed on caterpillars, flies, aphids and scavenge on carcasses; so it is not all bad! The workers chew up the protein and feed the larvae the chewed up food. The adults will eat some of the liquids from these chewed up delicacies, but they mainly feed on plant nectar. As they do this, they are also aiding pollination - another reason to let them be when possible. The adults require carbohydrates to maintain their zippy life style; thus the sweets on the table or heading towards your mouth are targets.  Stephanitis takeyai was introduced in eastern North America in 1946 from Japan and can be a serious pest in the nursery trade on Pieris japonica. The first record from BC was 2001 in Richmond on a P. japonica (Scudder 2004). This wee tingid was caught in a spider web, so we don't know what the host was on Leaning Oaks as we are Pierisless. We do have a few of the less common hosts, Rhododendron, Azalea and Salix. We will now be watching for yellowing and mottling on the upper side of the leaves, one sign that they are feeding on the underside. Apparently there can be four to five generations per year in Connecticut where there has been research done on this pest. I couldn't find anything on generation time for the population in the west. Scudder, G.. Heteroptera (Hemiptera: Prosorrhyncha) New to Canada. Part 2. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia, North America, 101, 2004. Available at: <http://journal.entsocbc.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/76>. Date accessed: 13 Feb. 2015.  Most years, Red-breasted Sapsucker (Sphyrapicus ruber) is an occasional visitor to Leaning Oaks, but a few times over the years this species has been on the property for extended periods and over the breeding season. Sapsuckers (there are 4 species in BC) feed on tree sap that they harvest by drilling net arrays of holes through the bark and into the cambium of a tree. Here the tree of choice is Douglas-fir and one of our trees has an large area of sapsucker wells on the trunk about 8 m off the ground. The sap attracts insects, which are also used as food by the sapsucker. Some winters, especially those with pronounced cold snaps, we have an influx of Red-breasted Sapsuckers. These spunky little beetles are found through the winter in the moist undergrowth searching out decaying plant matter or animal tissue to scavenge. This individual was cleaning the last of the meat, fat and soft bits from a young deer that had died at Leaning Oaks. Necrophilus hydrophiloides and others of their ilk play a very important role by recycling the nutrients through the coastal forest from the Alaskan panhandle to California. And cleaning things up!

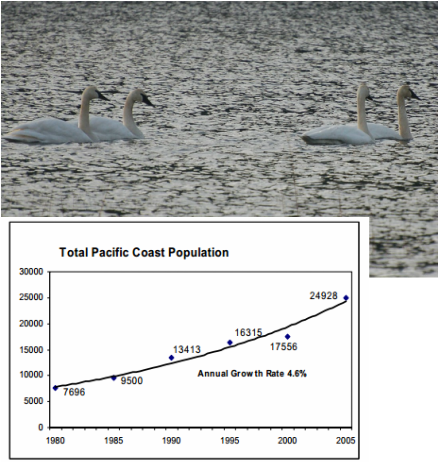

They are part of the Primitive Carrion Beetle family (Agyrtidae). They were once considered to be a subfamily of the Carrion Beetles (Silphidae). Look for the grooved elytra in the primatives to distinguish the families.  This caddisfly, (Halesochila taylori), usually found as an adult during the month of October is a dapper fellow, with Halloween colours of orange, black and white. It is sometimes called the October Caddisfly and is restricted to northwestern North America (Alaska, BC, Alberta, Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon). It is a species of of still waters; the larvae found in lakes and ponds. This adult was perched on a cattail leaf in the pond.  Sigh, maybe next pond will be this big! It would have to be big to hold the world's largest waterfowl. Beginning about mid November through to March or April we see or hear these bulky beautiful swans flying over Leaning Oaks on their way to or from a local wetland or field where they over winter. The trumpeting call is a wonderful reminder of how sometimes there really is good news and conservation success stories. By the early 1900s Trumpeter Swans (Cygnus buccinator) had been harvested to near extinction. In 1932 only 69 were known to exist! In the early '50s a few thousand were found in Alaska. And as you can see by the graph from the Pacific Flyway Council (2006) just the coastal population was 25 000 by 2005! There are still concerns about fragmentation of wintering habitat and development around their breeding grounds in the north - but they are doing alright now, with populations that continue to increase. |

AuthorsTwo biologists on a beautiful property armed with cameras, smart phones and a marginal knowledge of websites took up the challenge of documenting one species a day on that property. Join along! Posts and photographs by Leah Ramsay and David Fraser (unless otherwise stated); started January 1, 2014. Categories

All

Archives

May 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed