|

This small species of fly is a relatively recent arrival in British Columbia, with the first record a photo taken 2 June 2016 in Victoria by Eriko Yamamoto and posted on BugGuide by Talmage Bachman (https://bugguide.net/node/view/1544782) (Cannings and Gibson 2019). It belongs to a group of flies known as Flutter Flies some of which vibrate their wings when they are at rest or when walking. This species, (Toxonevra muliebris), is native to Europe and has a distinctive wing pattern with a loop marking on the forewing, making it one of the easiest Flutter Flies to identify.

Since the initial discovery there have been additional records of this species posted on Bug Guide and iNaturalist from Vancouver Island, the Gulf Islands, Greater Vancouver, south to the San Juan Islands and Seattle. This record can be found on iNaturalist here: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/286287362 . Almost all the records of this species in North America are from indoors, and our record from Leaning Oaks is no exception, this picture was taken in our kitchen. In Europe the species is found outdoors, with the larvae found under bark and is thought to feed mostly on beetle larvae. Indoor specimens in Europe are thought to feed on Dermestid (carpet beetle) larvae. It is assumed that the largely indoor records of this species in BC and Washington likely means that they are feeding on carpet beetle larvae here as well. BC has at least six native species of Flutter Flies (Cannings and Scudder 2005), but they are considerably more difficult to identify to species than this one. Folks that find this species are encouraged to post photos on iNaturalist or Bug Guide in order to document the timing and distribution of this new addition to our fauna and note if the specimen is found indoors or outdoors. Literature Cited Cannings, R.A. and Scudder, G.G.E. 2005. The true flies (Diptera) of British Columbia. In E-Fauna BC: Electronic Atlas of the Fauna of British Columbia [www.efauna.bc.ca]. Edited by B. Klinkenberg, 2018. Lab for Advanced Spatial Analysis, Department of Geography, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. Cannings, R.A. and J. Gibson. 2019. Toxonevra muliebris(Harris) (Diptera: Pallopteridae): a European fly new to North America. Journal of the Entomological Society of British Columbia. 116. Pp 64-67. https://journal.entsocbc.ca/index.php/journal/article/view/2473

0 Comments

I thought that I had just coincidentally happened upon a mosquito on a frog--but as it turns out, this mosquito (Culex territans) specializes in feeding on amphibians. I had no idea that this was a thing! It turns out that there are many species of mosquitoes that do. This species is found across much of the northern hemisphere, with records across southern B.C. The first time on Vancouver Island was noted in 2006.during surveys for potential vectors for West Nile Virus. Even though they were found, the incidence of this species feeding on mammals is very low with one study indicating that over 75% of al blood meals were frogs and toads, then next most frequently reptiles and then very few records of blood meals on mammals or birds.

They generally do not travel far from their breeding sites, where they prefer clean fresh water with some emergent vegetation. The females will lay their eggs in waterbodies where they have cued in on male frogs calling in the spring. They also are guided to their blood meals by listening for frog calls. The frog this one choose is a Pacific Treefrog highlighted as species #38 (https://leaningoaks.ca/a-species-a-day/38-pacific-treefrog). A few references: Bhosale, C.R., Burkett-Cadena, N.D. and Mathias, D., 2023. Northern frog biting mosquito Culex territans (Walker 1856)(Insecta: Diptera: Culicidae): EENY-803/IN1394, 3/2023. EDIS, 2023(2). Peach, DAH. 2018. An updated list of the mosquitoes of British Columbia with distribution notes. J Entomol Soc BC 115: 126–129 Stephen, C. Plamondon, N. and Belton, P. 2006. Notes on the Distribution of Mosquito Species That Could Potentially Transmit West Nile Virus on Vancouver Island, British Columbia," Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association 22(3), 553-556. The American Kestrel (Falco sparverius) is a relatively new addition to the bird species list for Leaning Oaks with our first records occurring in 2024. This is not surprising since the local trend for this species is a steady increase and resident birds are all around us. What is surprising is that this increase is bucking the widespread trend of a steady declines elsewhere in Canada. The decline in southern British Columbia since the 1970’s is over 75% (State of Canada’s Birds 2024). Many local birders believe the increase here is due to the arrival of a new prey source for the species, the now common and active nearly year round Common Wall Lizard. However, eBird trend maps show increasing numbers of American Kestrels just south of us as along the west side of Puget Sound, south to the Columbia River that forms the Washington-Oregon border. Those areas do not have Common Wall Lizards (yet). It is possible that these areas are benefiting from the increased Kestrel production on the east side of Vancouver Island or there is another explanation entirely for the regional increase such as benefits of warmer, drier summers.

Steller's Jays are the smallest and most brightly coloured of the corvids that are found here. Despite the fact that this species breeds nearby we have no records of this species from our property from May to mid August and the largest number of records come from the period September to December. Even within that period however there are marked differences in the numbers seen from one year to the next, with some years having almost no records and others having daily occurrences. We have three species of Corvids, or members of the crow family here at Leaning Oaks. The commonest are Common Ravens, the least frequently seen are Steller’s Jays and in between are American Crows. Our crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) were formerly considered a separate species, the Northwestern Crow but now the birds here are now relegated to subspecies (Corvus brachyrhynchos caurinus) status because of substantial genetic exchange with the birds of the interior. Here at Leaning Oaks they are present throughout the year, but almost always in small numbers. Based on Christmas Bird Count data crow numbers in British Columbia and on southern Vancouver Island show a long term decline.

This moth flies in October and November and is distinctively coloured from brick red to slightly pinkish - similar to the colour of the bark of an Arbutus (Arbutus menziesii) (species 30). In fact this larvae of this species feeds on Arbutus and Manzanitas (Arctostaphylos columbiana) on the island, and adds A. patula and A. viscida to its diet further south in Washington, Oregon, California and rarely, Arizona. This species was first described by Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. in 1903 (for more on the unusual life and hobbies of H.G. Dyar see Dyar’s Looper Moth species number 333).

The smooth larvae of this moth is brick red and brown and blends in with the bark of Arbutus trees and Manzanita bushes. Unlike most Orthosia moths this species flies in the fall, almost all the others in the genus are spring fliers. Rarely Orthosia mys overwinters as an adult and is seen in the spring. We could not find a common name for this attractive moth although many Orthosia moths have the common name of Quaker, so this could be called the Arbutus Quaker.. I was delighted the first time I saw what I thought was just a beautiful ice formation on the path near our house. When I found out that it was a fungus I was astounded and went running back to find it again to photograph it....but it was gone. A couple of days later on a cool morning we looked out the window and saw dozens of fallen branches and sticks covered in delicate white swirls! Most were on Garry Oak branches. This exquisite formation of ice crystals depends on the fungus, Exidiopsis effusa. It was only in 2015 that researchers in Europe identified the white crustose fungus as the key to the formation of these delicate crystals, although a German scientist in 1918 had determined that it was indeed some sort of relationship between a fungus and ice in the wood . According to local mycologist, Kem Luther, E. effusa has not been specifically identified in BC yet, and as we have several other species of Exidiopsis it may actually be a different species here.

The conditions have to be humid, only slightly below freezing, between 45 to 55 degrees in the North latitudes and in broad-leaf or mixed wood forests for Hair Ice to form and previous to the January 2024 bonanza, the humidity, temperature and fungus all aligned in this area in 2019. Not that we saw it--a bit like a cloudy solar eclipse day! According to Kem Luther, the formations will emerge from the same pieces of wood in subsequent years, yet another reason not to clean up fallen wood. Gabriola dyari, or Dyar's Looper Moth, is a moth in the family Geometridae and found from the Alaskan panhandle and British Columbia to California. The caterpillars feed on a variety of conifers, including Mountain Hemlock, Western Red Cedar, Silver Fir, Grand Fir, Subalpine Fir, Engelmann Spruce and most often in our area, Douglas-fir and Western Hemlock. They are a medium -sized moth with a wingspan of 25–30 mm. The forewings are variable from one individual to the next, but usually brownish gray with black speckling and lines. The hindwings are uniformly brownish gray except for a dark thin terminal line, which here is often broken, and appears as a dashed line. Adults in our area fly in late June throughout July. Larvae are active from May to July, after overwintering as an egg. Pupation takes place in a cocoon on a twig in August. The larvae come in two forms, one is grey with white blotches and is a bird dropping mimic. The second form is reddish with a tan head and with pale areas and this form mimics male conifer pollen cones.

Mid-career, Dyar was charged with bigamy having been married to a second person under an assumed name and fathering three sons. His first wife divorced him and he was dismissed from the USDA ”for conduct unbecoming a government employee”. He later legally remarried and adopted the three boys.

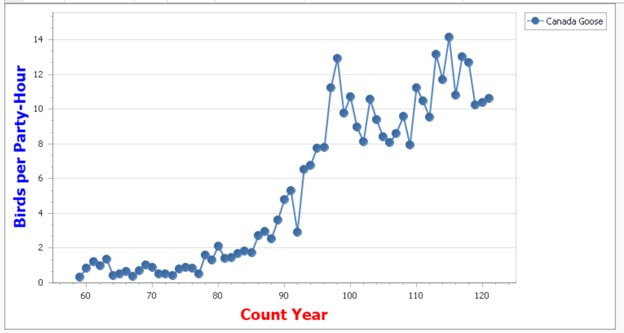

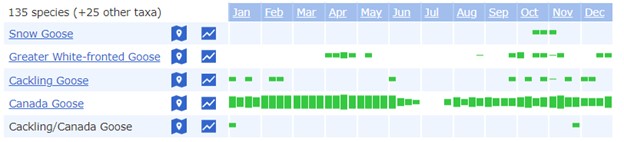

In 1924 a truck’s back wheels broke through some pavement in Washington D.C.. Upon investigation it was discovered that it had broken through the roof of a tile-lined tunnel. After some speculation in the press, Dyar admitted that he had yet another hobby building tunnels and had developed extensive labyrinths around at least two of the places he had lived. Some were up to 24 feet deep and equipped with electric lighting. For more information on the life of Harrison Gray Dyar Jr. click here and here. And if Stephen Heard is looking for material for a second volume on ”Adventurers, Heroes and Even a Few Scoundrels” that have lent their names to species, he may want to look at the person behind the name on Gabriola dayri, he appears to fall into all three categories. The Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) on the Saanich Peninsula has an interesting history that is documented in a paper by Neil Dawe and Andy Stewart. Prior to the 1970’s the Canada Goose was mostly a migrant and winter visitor to our part of the island, although small numbers of the “Vancouver” subspecies of Canada Goose nest on the northern part of the island. There were several small introductions of Canada Geese to the southwest coast of the British Columbia in the late 1920s and early 1930s and then again in the 1970s when larger numbers of Canada Geese were introduced to the lower mainland and S.E. Vancouver Island. These geese came from a variety of places and did not include the subspecies that was breeding on the island. The earliest documented release of Canada Geese on Vancouver Island was in 1929 when 16 Canada Geese were let loose from a game farm operated by the province at Elk Lake on the Saanich Peninsula. These introduced birds were augmented by other introductions and reproduced rapidly. By 1958 there were 200 Canada Geese on Elk Lake and were seen moving between Elk and Quamichan Lake in the Cowichan Valley. The earliest breeding record I have found for the Victoria area away from Elk-Beaver Lakes was in the notes from the naturalist Tom Briggs that I have entered into eBird. On May 16, 1960 he wrote, “Met Dave, Ruth [Stirling] and Diedre; they had seen a goose on a nest ....on top of an old snag" ( https://ebird.org/checklist/S27964036) and for the next few days Tom made repeated trips to the Highlands to show others this nest, an exciting find in 1960! In the fall and winter our resident birds are augmented by migrant and wintering geese that breed further north. Many northern hemisphere geese (Canada, Snow, Ross’s, Cackling, Greater White-fronted, Red-breasted, Barnacle, Brant and Pink-footed) are on the increase. It is estimated that there are three times as many geese in North American as there were 30 years ago. (For a review of trends in northern hemisphere geese click here). The increase in the combination of resident geese and overwintering migrants can be seen below in the graph for Canada Goose for the Christmas Bird Count for the Victoria area. Here at Leaning Oaks, we have records of Canada Geese for most of the year, except for the first three weeks of July. This is the period of the year where our resident Canada Geese moult their flight feathers and cannot fly. Since there are numerous records from nearby Prospect Lake during this period, and that lake is within earshot, they are clearly quieter during this period as well.

As large as a crow, Dryocopus pileatus is Canada’s largest woodpecker and a year-round resident here at Leaning Oaks. Few days go by when we don’t see one or more of these spectacular birds at our suet feeder, or hear the high pitched and nasal “cuk, cuk, cuk, cuk, cuk” call of this woodpecker. Masters of wood processing their presence can be detected by the large feeding holes they create in trunks of trees. These can be rectangular in shape, particularly when they are searching for ants in Western Red Cedar trunks. In fact, they can be so rectangular I have encountered people that refuse to believe they aren’t human made. It isn’t the only type of feeding hole they make and here our largest Douglas-fir trees have large irregular holes in the bark in the lower trunks where Pileated Woodpeckers have been searching for the grubs of wood boring beetles. They also feed heavily on Carpenter Ants and Dampwood Termites .

Pileated, by the way, means having a crest covering the pileum (top of a birds head from the base of the bill to the nape). The best part about these brilliant gushy looking fungi is that add a much needed splash of colour midwinter. Dacrymyces chrysospermus (syn. D. palmatus) is common on conifers and often is found on rotting wood. They are generally about two to three centimetres across and have as one key refers to the orange blobs, "brain-shaped or coralloid lobes". These fungi can dehydrate to an inconspicuous little dark may and then rehydrate when there is enough moisture to do so. This can happen repeatedly. Orange Jellies occur over much of North and Central America and across Europe.

The somewhat similar Witches Butter (Tremella mesenterica) is found on hardwood and has other structural differences. When you are looking for keys to our west coast fungi, do head to the South Vancouver Island Mycological Society website. The jelly key is here. Or more precisely the Trial Field Key to the Pileate Jelly Fungi in the Pacific Northwest by Ian Gibson. Of the nine species of finch that we have recorded so far here at Leaning Oaks, the Pine Siskin (Spinus pinus) is the most abundant and constant on the property, with records from every week of the year. That being said, it IS a finch, a group of birds known for nomadism and irruptive behaviour and that has been in ample evidence this year. Large numbers of Pine Siskins have been present for months now and and feeders have been very busy with this species since last September. Flocks of siskins have been passing overhead nearly constantly and their upward slurred calls are a nearly constant sound during daylight hours here ever since June of 2020.

The movements of Pine Siskin are, at least in part, linked to food availability and they wander widely when food crops are low in the northern forests. These irregular movements are layered on top of a seasonal migration, making generalizations about siskins movements difficult to describe. They feed on a wide variety of seeds, including thistle and dandelion, conifers, alders and birches. Their use of bird feeders at Leaning Oaks is variable, some years they are present nearly constantly, and other years they might not use our feeders much or at all. Presumably in years where there are heavy conifer or alder seed crops they may not need to forage at bird feeders. They also take green buds and a variety of arthropod prey. Their thin, pointed bills make dealing with very hard seeds difficult and they often use broken seeds left by other finches. Anyone with a feeder will notice that Siskins are remarkably variable in patterning, especially the amount of yellow visible on the wings. Gender is not reliably determined by either plumage or size. Females are fed on their nests by males and therefore seldom leave the nest during incubation. Adults feed their youngsters by regurgitation of a thick yellowish or greenish paste. Young leave the nest on 13 to 17 days after hatching. Dicranoweisia cirrata is epiphytic and commonly found on tree trunks or wood in early stages of decomposition or fence posts and wooden signs. It is also found on concrete or stone, particularly close to the coast. . Another common name is Curly Thatch Moss. When it dries in the summer the leaves are twisted and contorted. In the winter they are smoother and upright as are the sporophytes.

It is found on Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii the mainland coast. There are observations on iNaturalist from the interior of BC, but they have not been identified yet, so it will be interesting to see if it found further afield once the moss experts ID these. The authors of Plants of Coastal British Columbia (Pojar and Mackinnon) indicate that it most readily identified by habitat.and then a bit disparaging "and its lack of impressive size, colour or morphology". Damned by faint praise. Here at Leaning Oaks, we most often encounter Hermit Thrushes (Catharus guttatus) in the late fall and early winter, less often in the later winter, and then an increase again during spring migration in March and April. We don’t get to hear its beautiful song here very often, with the exception of the spring of 2013 when a male set up territory on the property and often sang repeatedly for over an hour early in the morning. Very early in the morning in fact. Early morning singing is a feature of Hermit Thrushes during their breeding season and Hermit Thrushes and American Robins both have adaptations in eye structure thought to enable them to detect early morning light better than other bird species that start singing later in the day.

The Hermit Thrush is aptly named, 97% of the sightings we have of Hermit Thrush at Leaning Oaks are of a single bird. The Questionable Stropharia, Stropharia ambigua, is a relatively common fungus found on the wet west coast. It is found most commonly under conifers, but may be in mixed forest in rich humus, providing a dash of light in the dark, Here on Leaning Oaks it was found near Douglas-fir. It is only found on the Pacific coast from Alaska to California. It is relatively distinct with the cottony white veil over the tan or yellow cap and the shaggy white stalk. It can be found singly or in small groups, both having been seen here. Strophus in Greek means belt, and for this genus refers to the distinctive membranous ring on the stipe.

The description of this species in the nearly 1000 page tome, "Mushrooms Demystified" by David Arora is full of superlatives that you may or may not agree with. "There is nothing ambiguous or questionable about this elegant, stately fungus. It is our most common woodland Stropharia and at its best is one of the most exquisitely beautiful of all mushrooms--well worth seeking out." This past year, 2020 was a year of discoveries and iNatting. We were challenged to do an iNaturalist project where we documented every species possible that we could within a five mile or 8 kilometre radius from our house. This was a challenge posed by a colleague in Ontario and many signed in to play along. What a great thing to do when you couldn't travel far anyhow. Because of the somewhat um, competitive nature of this challenge, I learned a lot about groups that I had not particularly paid a lot of attention to before, like mushrooms. We were excited to find this attractive moth under our porch lights in August. Leah had been working on assessing the status of all the Lepidoptera (Moths, Butterflies and Skippers) of British Columbia and we had read about this species (Elophila icciusalis), and were fascinated by the aquatic larvae portion of its life cycle. The larvae feed on duckweed, Buckbean, pondweeds and aquatic sedges. Our pond now has a flourishing cover of (#253) Common Duckweed which we suspect has, in turn, attracted this species to take up residence on our property.

BC records for adults of this species are from June and August. It is a member of the Crambidae family, or Snout-Moths. Larvae and pupae are in cases made of aquatic vegetation, similar to those made by some caddisflies. The background colour of the adult varies from tan to yellow to orange. The Pondside Pyralid Moth is found across much of North America. This seed-bug, Rhyparochromus vulgaris was first found in North America in Seattle in 2001 and by 2004 was being found throughWashington and Oregon. It occurs naturally in throughout Europe, including south to the Mediterranean region. In BC there is a 2013 record from a Langley nursery. The first record from the interior of BC was from Creston in 2015. This species overwinter as adults, feed on seeds and will enter buildings in large numbers. This was just a lone individual.

The genus means "dirt-coloured" thus the rather blah English name. This is a very attractive small moth is attracted to the lights on our porch on summer evenings. The yellow colour is easily mistaken on a branch for a yellowed and wilted leaf. It has a variety of english names, including the Pink-bordered Yellow and the Two-pronged Looper. The latter is from the two spikes on the caterpillar, which adds to its effectiveness as a accomplished twig mimic. Click here for an excellent image of the caterpillar. Sicya macularia caterpillars feed on a variety of deciduous shrubs including alder, blueberry, buckthorn, currant, false azalea, poplar, shrubby cinquefoil, spiraea, and willow.

Alaska Onion Grass (Melica subulata) is one of the few native species of grass we have at Leaning Oaks. Commonest under the shade of some of our Douglas-fir it is an indicator of a rare plant community on southern Vancouver Island. Onion grasses are so named for the bulb like corm found at the base of the stem. The corm of this species is said to be edible, with a nutty flavour, although I haven't tried it myself. This is a perennial grass that spreads by rhizomes. There are two other species of Melica on southern Vancouver Island, but neither of those species produce the onion-like corms.

This micromoth is a variable, colourful moth with long antenna and a distinctive shape. Carcina quercana is native to Europe with a small range in western North America where it is introduced. It was first found in Victoria in 1920 and there are records from Victoria to Port Alberni, the lower mainland and the Seattle area in Washington State. Most references suggest it is a specialist on oaks, and indeed one of the other names for it is the Oak Skeletonizer Moth. In fact however, it appears to use a wide variety of host plants for its caterpillars, including beeches, blackberries, apples, chestnuts and recently in Victoria, it has been found feeding on Snowberry.

The larvae are small green caterpillars found on the underside of leaves, usually protected by white webbing. Another common name is Long-horned Flat-Body and the "flat body" is a characteristic of the family, the Depressariidae (which means flat). It can be tan, pinkish, orange or brown, usually with a small yellow line at the wing tip and a larger yellow spot on the wing and very long antenna, sometimes longer than the body of the moth. |

AuthorsTwo biologists on a beautiful property armed with cameras, smart phones and a marginal knowledge of websites took up the challenge of documenting one species a day on that property. Join along! Posts and photographs by Leah Ramsay and David Fraser (unless otherwise stated); started January 1, 2014. Categories

All

Archives

May 2025

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed